Why does Richie from Bottom resonate with me?

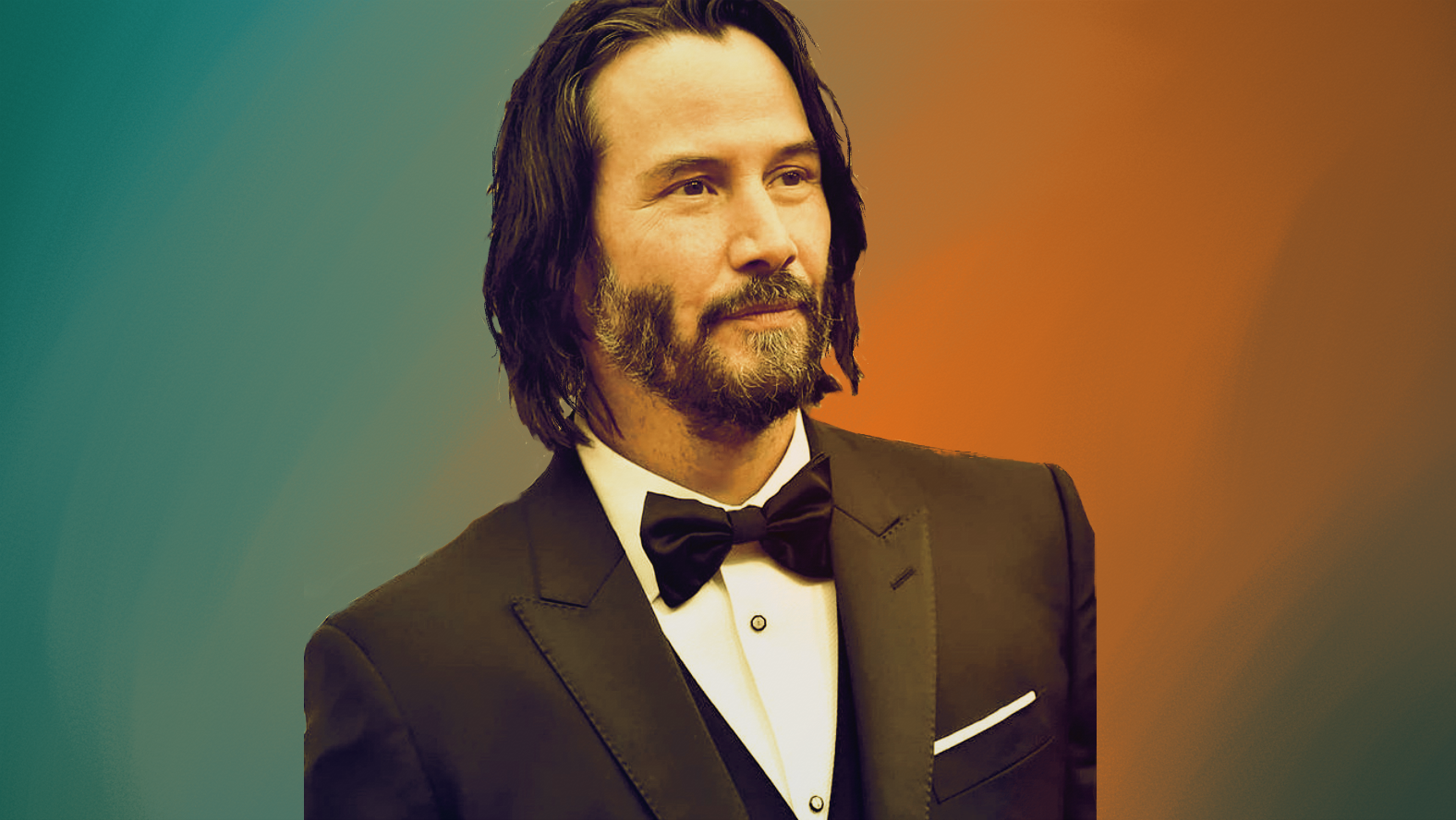

It can’t just be the brilliant performance of Rik Mayall. Alan B’Stard, Rick, Micky Love, Drop Dead Fred are all brilliant characters, brilliantly realised, and I think about them a lot.

But I think about Richie. Every. Single. Day.

I’ve thought about Bottom so much over the years that I decided to write a book about it. I gave it the very grown up title Proctology: A Bottom Examination, and in it I explored the events and cultural changes that led Rik and Ade into comedy, informed their early work, and culminated in a bleak sitcom warning about the dangers of nostalgia, that skewered toxic masculinity before it was even a thing, and I placed it in the context of a post-Thatcher Britain. It’s no wonder I wanted to write something about it here.

But I thought I’d written everything I could about Bottom.

And still, I think about Richie. Every. Single. Day.

In recent months, I’ve been coming to terms with the fact that I probably have ADHD. Realising this as an adult in my mid-forties has been quite the head fuck, recognising that behaviours I believed to be neurotypical are no such thing, and realising that my bouts of inactivity aren’t signs of laziness or fatigue, they’re a symptom. Being exhausted by socialising, feeling over stimulated and anxious in the supermarket, being overwhelmed by last minute change, having a favourite piece of Lego to fiddle with – it’s always there, and sometimes, often, the only thing I can do is dissociate and stare at the TV for hours, day after day.

This is all to frame an epiphany.

Richie from Bottom resonates with me because he’s everything in my brain made manifest.

To be clear, this isn’t an exercise in diagnosing a fictional character, I mean, what would be the point? It’s merely using a diagnostic tool to try and understand why I related to, and continue to relate to a completely made up person.

People with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder have difficulty concentrating and focusing, and struggle with hyperactivity and impulsiveness. Not everyone falls into both these categories, and by adulthood, many people have learnt to mask these behaviours (which in itself is exhausting), and develop strategies and coping mechanisms to make their lives ‘easier’. According to NHS online the main signs of inattentiveness are:

- having a short attention span and being easily distracted

- making careless mistakes

- appearing forgetful or losing things

- being unable to stick to tasks that are tedious or time-consuming

- appearing to be unable to listen to or carry out instructions

- constantly changing activity or task

- having difficulty organising tasks

The main signs of hyperactivity and impulsiveness are:

- being unable to sit still, especially in calm or quiet surroundings

- constantly fidgeting

- being unable to concentrate on tasks

- excessive physical movement

- excessive talking

- being unable to wait their turn

- acting without thinking

- interrupting conversations

- little or no sense of danger

If you want to see half an hour of someone exhibiting all of these behaviours, just watch the episode Culture. It’s brilliant, and you won’t regret having watched it, or re-watched it.

How long does it take Richie to settle down and play chess? How many side-quests does he go on before they start playing? How often is he back up on his feet, pacing and talking excessively?

‘Richie, I’ve been here since ten o-clock last night, it’s five o’clock in the morning … I’ve explained the rules of chess to you one hundred and twenty four times, and I’m buggered if I’m going to let you delay the game another ten minutes while you scan through a few back copies of Amateur Photographer. OK?’

For larks (it’s good for morale), let’s ask Richie some of the questions on the Barkley Deficits in Executive Functioning Scale – a questionnaire used to evaluate the executive function of adults in daily life. Presented with a statement, the subject is then asked to self-report how often this happens, on a scale of Never, Sometimes, Often, or Very Often.

‘Find it difficult to tolerate waiting; impatient.’

In series three’s Break, Richie absolutely cannot wait to go on holiday. This bottle episode is a lovely little study on the bleakness of hope, letting us revel in the claustrophobia of excitedly waiting for something. Some people with ADHD describe waiting mode, which means if they have something coming up, an appointment, it becomes very difficult to do anything other than just wait for the time. I do this, and I get incredibly restless, urging myself to do something, anything, but utterly incapable of acting.

‘Overreact emotionally.’

In Accident, when Eddie claims Richie has forged his own birthday cards, Richie massively overreacts to this slight. Likewise, in the pilot episode Content, he evicts Eddie after an argument. He overreacts to women showing interest in him, he overreacts to being accused of using an art book for onanism, he overreacts to everything. Richie would tick Very Often to all twelve questions in the emotional regulation section.

‘I cannot resist doing things that produce immediate rewards even if they are not good for me in the long run.’

We’ll have no jokes about masturbation thank you. But the way he sabotages his own party because he needs the instant gratification of acceptance, also in Accident, is an excellent example of this.

‘More likely to drive a motor vehicle much faster than others (excessive speeding)’

I don’t do this, and Richie doesn’t drive. Except once, in Finger, when he impulsively steals a car and drives it recklessly through the countryside.

‘Trouble following the rules in a situation.’

Having had the rules of chess explained to him exactly one hundred and twenty four times, Richie then just makes up his own game of chess, culminating in one of the best comedy fights committed to video tape.

‘Find it hard to focus on what is important from what is not important when I do things.’

In ‘S Up, Richie can only focus on his white coat, and the insistence that Eddie wear a brown one – culminating in forcing Eddie to wear his jacket backwards.

‘Easily distracted by irrelevant events or thoughts when I must concentrate on something.’

Having been put in charge of the shop downstairs, also in ‘S Up, Richie wanders around lost in a fantasy of his newfound power, beheading little Johnny from the flats and reporting him to the Feds.

There are countless examples of everything on the scale, liberally strewn about every single episode.

Perhaps the most striking thing to me about Richie is the way he stims.

‘Self-stimulatory behaviour, usually known as stimming, refers to atypical movements, sounds or behaviours that are repeated as a way to cope with overstimulation, or provide needed stimulation. Neurodivergent individuals can often use stimming as a protective response to environmental or circumstantial factors that may cause them to feel nervous, anxious or impulsive. Stims can also soothe the body and allow for increased engagement with the environment and people around you.’ (Neurospark)

Think of Richie’s over-excited laugh, for example.

But he has others.

He paces around a lot, he steeples his fingers and moves them in a wave, he repeats words (‘baaaam-boo’), he repeatedly flips through books, he plays with his hair, he strokes objects as he passes them, he stares into space, he rubs his hands on his clothing, he picks up objects and comments on them, he picks at his own fingers, and he bites his nails, to name just a few. None of these things are played for laughs, none of them develop the plot, they are just part of who Richie is, moments Rik found on set in front of the camera, and each and every one of them jumps out at me every time I watch. I recognise my own stims in them. Talking to myself as I boil the kettle. Repeating a word to feel it in my mouth. Using accents. I see so much of my own self in Richie, it’s no wonder he has been such a profound part of my psyche for the past thirty plus years.

Richie lives deep inside me (oo er), and every day he’s fighting to erupt (oo er), and I have to use all my energy to beat him off (oo er), because walking around like him in front of everyone would be … let’s say, frowned upon. Richie can’t function in the ‘real’ world, and so it’s incredibly comforting to see a depiction of him on the television (a box that has meant so much to me over the years). Richie makes me feel seen.

In fact, let’s be honest, Bottom is the sitcom embodiment of the inside of my own head. It’s very loud, and it’s very messy. Their flat could well be a visual representation of my own brain.

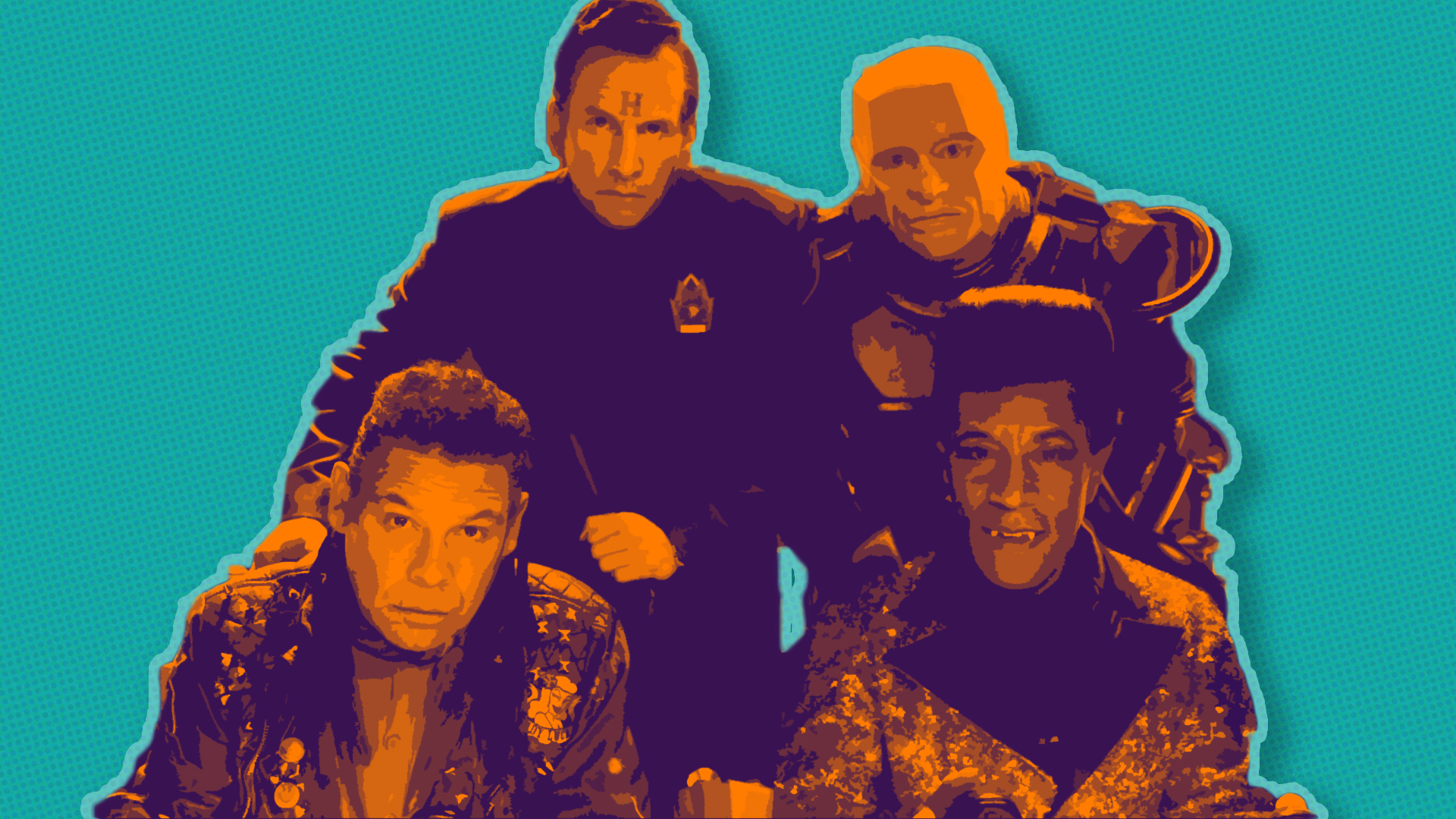

And what about Eddie?

That was my final epiphany. Eddie’s inside my head too. Eddie is my inner critic. He’s there to heckle Richie, to roll his eyes, to sit in silence judging while Richie thunders around a room. He’s the one exhausted by Richie, who needs to sit in a quiet room all day watching television, the one who can’t motivate himself to do anything, no matter how much he wants to. Slime in this ear, slime in that ear, JUST STOP TALKING. Eddie hates Richie, but he can’t live without him. Eddie loves Richie, but he drives him to the brink. Eddie needs Richie, and Richie needs Eddie.

Together, they live in my head.

Thankfully for them, it’s rent free.